Refundable Benefits Like EITC and CTC Now Off-Limits, Leaving Millions of Low-Wage Workers Scrambling Amid Holiday Crunch

The faint scent of pine from a corner Christmas tree mingled with the sharp tang of instant coffee in Rosa Hernandez’s East Los Angeles kitchen on the morning of November 29, 2025, as the 38-year-old house cleaner pored over her tax folder, her pencil scratching notes on last year’s refund that had meant new shoes for her three kids and a buffer against unexpected car repairs. Hernandez, who crossed from Mexico in 2010 seeking work to support her U.S.-born children, had always filed faithfully with an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN), her $28,000 annual earnings qualifying her for the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and Child Tax Credit (CTC)—lifelines totaling $2,500 that turned scraped-together wages into something resembling security. But as Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent’s November 28 announcement scrolled across her phone—proposed regulations barring undocumented immigrants from refundable tax credits, effective immediately under President Trump’s directive—Hernandez felt a familiar knot tighten in her chest, her hands pausing on a crayon drawing from her youngest. “That money’s not luxury—it’s lunch, doctor’s visits, a chance to breathe without debt calls,” she said, her voice soft with the quiet desperation of a mother who rises at 5 a.m. for back-to-back cleans. For Hernandez and over 2 million non-citizen filers who claimed $4.5 billion in such credits in 2023 per IRS data, the cutoff arrives as a gut-wrenching blow, stripping a modest reward for honest labor and forcing families to confront holidays—and futures—with one less thread to hold on, a policy shift that promises fiscal prudence but extracts a human toll in the daily grind of making ends meet.

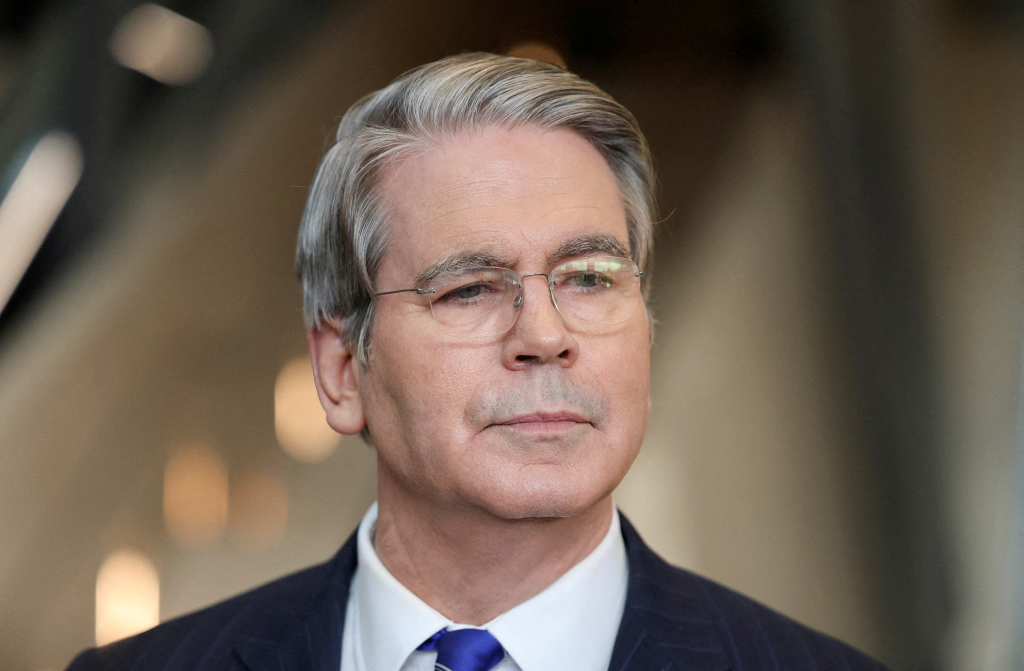

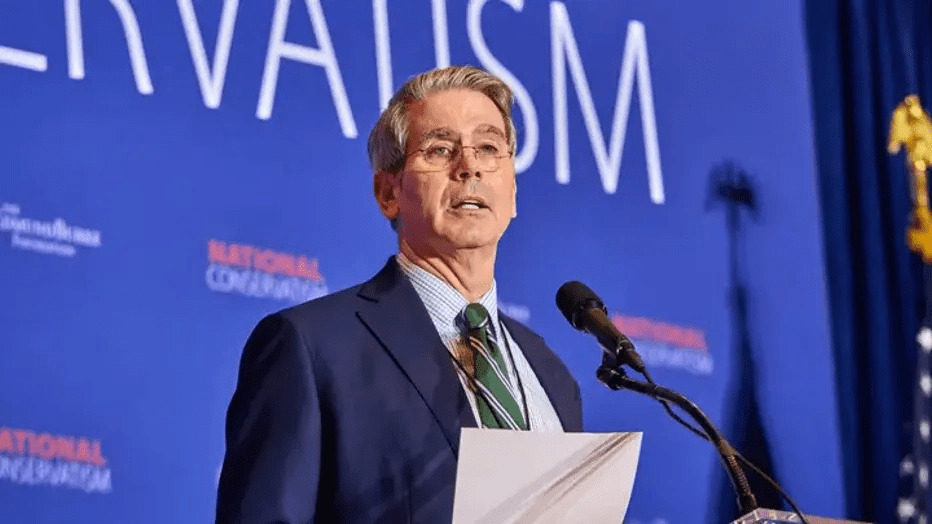

Scott Bessent, the 62-year-old hedge fund veteran confirmed as Treasury secretary in March 2025, unveiled the regulations in a November 28 statement from his Foggy Bottom office, framing them as a clarification of long-standing law to “enforce the law and prevent illegal aliens from claiming tax benefits intended for American citizens.” The rules target refundable portions of four key credits—the EITC (up to $7,430 for families with three or more children), Additional Child Tax Credit, American Opportunity Tax Credit, and Saver’s Match Credit—reclassifying them as “federal public benefits” ineligible for undocumented claimants or other non-qualified aliens, per a Justice Department reinterpretation sought by Treasury. Previously, ITIN holders could access these if they filed taxes and met income thresholds, a practice rooted in 1996 welfare reforms but expanded to encourage compliance, allowing 4.3 million non-citizens to claim $8.9 billion in 2023 despite restrictions meant for citizens and qualified residents. Bessent, a former Soros Fund alum whose Wall Street savvy guided Trump’s tariff revenues to $215 billion this fiscal year, emphasized the move’s precision: “This ensures taxpayer dollars support those who contribute to our system, not circumvent it.” For Hernandez, who filed her 2024 return in February for a $1,800 EITC, the change means amending claims or facing audits, her caseworker warning of “months of limbo” that could wipe out savings for her 12-year-old’s braces or her 8-year-old’s asthma meds.

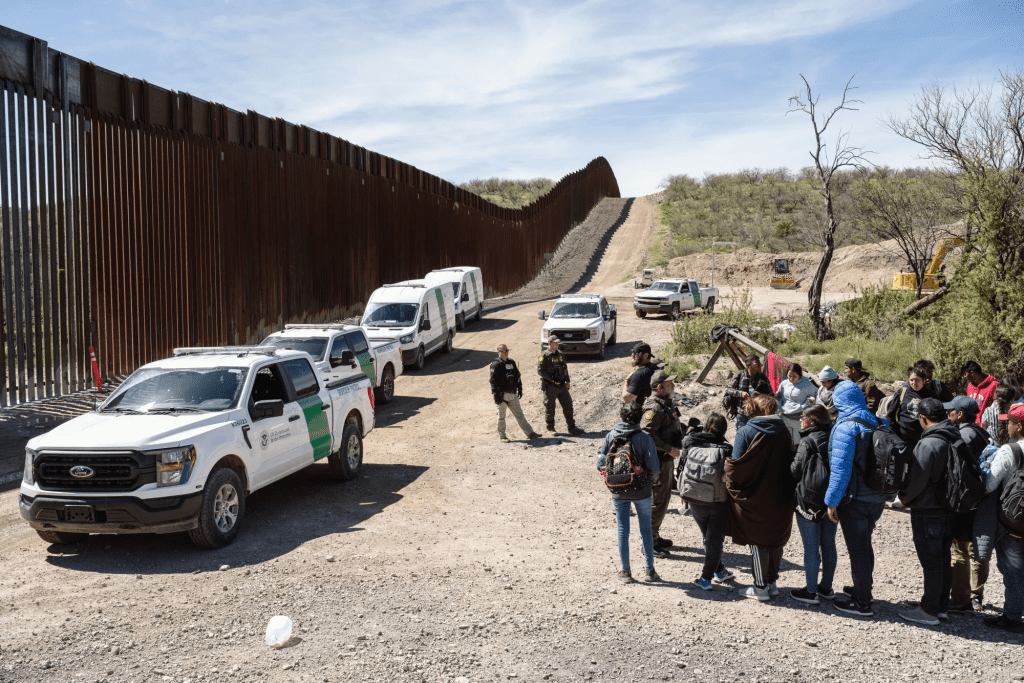

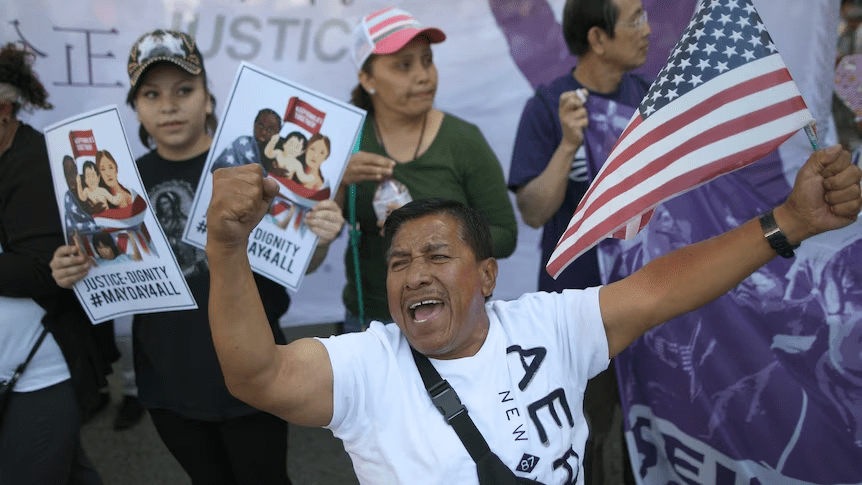

The policy’s origins lie in the Trump administration’s “sovereignty agenda,” a post-inauguration blueprint to reclaim federal resources amid a $1.8 trillion deficit, with Bessent’s November 19 Treasury release kicking off a series of executive tweaks. Undocumented workers, ineligible for Social Security or Medicare despite contributing $13 billion in payroll taxes annually per the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, have long used ITINs to file and claim refunds as a rare equity—a 2023 ITEP study found they pay $27 billion in state and local taxes yearly, their credits a modest return on that investment. The cutoff, part of broader cuts like TPS terminations for 1.2 million, could slash $4.5 billion in refunds, hitting low-wage sectors where undocumented labor fills 25% of agriculture and construction roles. For Hernandez, the EITC—up to $7,430 for her family—has meant school clothes instead of skipped meals; without it, her $2,300 monthly take-home stretches thinner, forcing choices between rent and relatives’ couches. “My oldest turns 18 next year—college dreams? Gone if we can’t afford basics,” she confided to a community center group, her hands folding a child’s drawing of a family picnic, the crayon lines a fragile dream amid the forms’ fine print.

The human ripple reaches heartland towns where immigrant labor props up farms and factories. In Iowa’s corn belt, 45-year-old Guatemalan farmhand Elena Vasquez, who arrived in 2012 fleeing domestic violence, relies on the CTC for her two U.S.-born daughters’ soccer fees and braces. “I pick beans from dawn to dusk—$12 an hour, taxes taken. That credit’s my only savings,” Vasquez said over a church potluck in Des Moines, her calloused hands serving pupusas to neighbors who know her as the reliable hand in the fields. Vasquez’s family, one of 4.4 million mixed-status households per Urban Institute data, treads a fine line—contributing $11.7 billion in Social Security taxes without benefits, their refunds a rare windfall. The cutoff, tied to Trump’s “reverse migration” vow on November 27, could slash $4.5 billion in refunds, hitting low-wage sectors hardest where undocumented workers comprise 25% of agriculture and construction labor. For Vasquez, whose husband faces deportation proceedings, the loss means dipping into emergency funds for rent, her daughters’ questions—”Why no Christmas lights this year?”—a dagger of parental guilt.

Bessent’s regulations, proposed under 1996 welfare reform authority, clarify eligibility to “citizens and qualified aliens,” excluding ITIN users from refundable portions while allowing non-refundable credits for taxes owed. The Treasury, facing deficits, frames it as prudence—”taxpayer dollars for taxpayers”—but advocates like the National Immigration Law Center argue it punishes compliance, as 4.3 million ITIN filers paid $23.6 billion in taxes in 2021. Trump’s directive, issued November 19 amid the Guard shooting’s aftermath, aligns with his agenda—pausing Afghan visas and reviewing 76,000 green cards—a cascade that could strip $8.9 billion in credits yearly. For Hernandez, who filed her 2024 return for a $1,800 EITC, the retroactive risk means audits, her caseworker warning of “months of limbo.”

Reactions poured in like a tide, gratitude laced with bitterness. In a Toledo diner, Trump supporters like 62-year-old Jim Hargrove passed phones over pie. “Overdue—Biden’s autopen wasted billions. Trump fixes it,” Hargrove said, quoting “recovery” as the room nodded on housing strains. Online, #UndoBiden trended with 2.8 million posts, supporters sharing “revitalized budgets” from Ohio factories.

For others, profound ache, thanks soured by loss. In a Little Haiti church, 200 prayed in Creole, Rev. Jean-Marc Pierre linking arms: “We’ve built lives—this isn’t thanks; it’s tearing.” Social media, under #SaveOurPromises, trended with 2 million posts—families sharing forgiveness letters.The blueprint targets 1.2 million affected, revoking citizenship for “terrorism”—INA gray area sparking ACLU suits. “Recovery from damage,” Trump wrote, citing 2.5 million encounters. Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene hailed “sovereignty,” her post 1.2 million likes. Sen. Jeanne Shaheen decried “overreach,” her SIV bill stalling. As December dawns, reviews for January 2026 unfold in reckonings—families packing, supporters toasting. Trump’s words, raw as holiday talk, invite reflection: Gratitude for welcome, tempered by protection. In Miami churches and Minneapolis markets, thanks endures—in hands across tables, family the true feast.